Introduction

Location of Thacker Pass

In late March of 2021, PLAN staff and supporters visited Thacker Pass where a land occupation protest is ongoing in opposition to a massive Canadian owned lithium mine proposed for the site. Thacker Pass is on Northern Paiute lands in northern Humboldt County near the border with Oregon. It is just to the south of the Fort McDermitt Paiute Shoshone Reservation, and west of the quiet ranching community of Orovada. The mine was fast tracked for approval in less than a year through the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) based on Trump administration executive orders. Such a timeline is unheard of for complex mining projects which often result in intergenerational impacts.

In addition to the land occupation, Great Basin Resource Watch, Basin and Range Watch, Western Watersheds Project, and Wildlands Defense filed a lawsuit with the BLM challenging the legality of the environmental review process. A local rancher also filed a lawsuit challenging the process.

Description of Mine Proposal

Panorama of Thacker Pass

Lithium Americas Proposal

Thacker Pass, pictured above, is a low area with a sagebrush ecosystem connecting the Quinn River Valley and Kings River Valley. This region is an important winter habitat for mule deer. The Montana Mountains to the north are home to sage grouse breeding grounds and golden eagles. The area is rich with Paiute history that spans thousands of years of sustainable occupation; something our western society is failing to achieve. The lithium deposit results from ancient volcanic activity which also produced significant amounts of obsidian which served as an important stone tool material.

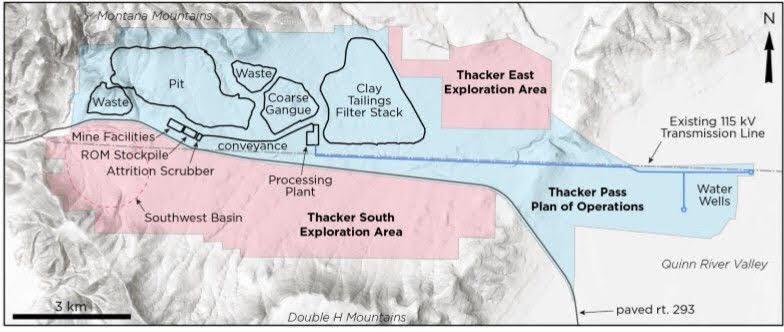

The second image is what Lithium Americas plans to do to this area, which entails the entire panoramic photo above. A massive open pit would be the center of the project and waste rock would be piled on either side. The waste rock to the west of the pit would be adjacent to Thacker Creek which flows from springs in the mountains and is carpeted with watercress.

The company claims they will fill the open pit after mining, which is not required by Nevada or federal law! However, materials under the earth take thousands of years to stabilize. When brought to the surface and exposed to air/water this material becomes dangerous, and can’t return within a human lifetime. Independent analysis from geochemists at Great Basin Resource Watch points to groundwater contamination as water flows through the reclaimed pit area, and would require at least 300 years of active water pumping and treatment post-mining.

The company’s process to isolate the lithium is based on using sulfuric acid. So, there would be an industrial sulfuric acid plant on site. Many trucks would be driving through the small community of Orovada daily, carrying hazardous material to support this process, and the industrial plant would produce sulfur dioxide emissions which are noxious.

With all of this in mind, we traveled north from Reno to meet with community members from the area. It can be hard to know what is really at stake reading about these things from afar, yet impacts become much more tangible when you hear from the people who call this place home.

Environmental Justice Webchat

Protest Occupation Camp on the Land Proposed to be an Open-Pit

(left to right) Myron Smart, Will Falk, and Ian Bigley

We arrived at the camp in the afternoon, and met with Myron Smart, a respected knowledge keeper from from the McDermitt Tribe, and other folks at the occupation site. Since there is good cell phone reception there, we were able to host our monthly PLAN Environmental Justice Webchat from the site. We invited Nevadans to tune in, and hear directly from Myron and others about what they are experiencing, what is at stake, and why this place matters.

Cordero/McDermitt Mine

Sunrise at Thacker Pass

We woke with the sun the following morning. After warming up around the fire and eating a little breakfast, we drove north from Thacker Pass to meet Myron in McDermitt. He agreed to show us around the Cordero/McDermitt mine; a mercury mine perched on the mountainside above the reservation which received a final closure report in 1994.

Cordero Mine looking Toward McDermitt

Despite the issuance of a closure report the site continues to affect people in the area. Mine waste material was used in construction throughout the adjacent reservation including at the local school. This resulted in dangerous levels of mercury and arsenic in the soils exceeding EPA limits. In 2012 the EPA filed a Unilateral Order to Sunco and Barrick Gold to participate in the cleanup however both companies declined to participate in the work. The United States spent $1.2 million in taxpayer money to address this waste through Superfund monies despite the site not being on the Superfund National Priorities List. To this day, the site continues to pollute groundwater forcing McDermitt residents to rely on bottled water. We also heard air quality concerns about the dust that blows off the site to the reservation.

The story of this mine makes the community’s concerns with Thacker Pass far to real. Folks worry about water, air, land, and health. The air and water impacts that would come from Thacker Pass are not imagined fears to this community. Similar impacts already exist from the Cordero/McDermitt mine, providing an example of the kind of long-term pollution that locals can expect from the current mining proposal.

Abandoned Mine Sign at the Cordero/McDermitt Mine

Despite the 1994 closure report, significant portions of the site appear to have seen no reclamation, and instead are fenced off and posted with signs from the Nevada Division of Minerals Abandoned Mine Lands Program. This program addresses dangers from the estimated 200,000 abandoned mines in Nevada, which often consists of fencing them off, and posting a sign.

Underground Tunnels at the Cordero Mine

Mine Waste Left Uncontained at the Cordero/McDermitt Mine

Mine Waste in Abandoned Buildings at the Cordero/McDermitt Mine

Social Impacts

Canyon at McDermitt Creek

As we left the Cordero/McDermitt mine, taking a deep breath of clean air once off-site, we pulled to the side of the road near a canyon with steep walls and cliffs. Myron asked if we wanted to learn where the name McDermitt comes from. Colonel McDermitt led the cavalry engaged in the attempted genocide of Paiute, Bannock, and Shoshone Peoples based in the area. The canyon we stopped by is known as McDermitt Creek. In 1865, a form of community justice was enacted when Colonel McDermitt was drawn into the canyon and ambushed.

No More Stolen Sisters Banner at the Protest Camp

The story above of settler violence and Indigenous resilience is not an artifact of the past. Settler commodification of the land continues to be closely tied to physical violence. In addition to the concerns of pollution and wildlife loss, social violence is a fear should the Thacker Pass mine be built.

The crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) refers to the high rates of murder, kidnapping, and sexual violence enacted upon Indigenous women. MMIWG is known to be closely linked to extractive industries. This is due to the large influx of primarily male workers into rural areas for extraction. Nevada’s failing education system means that a lot of the skilled labor relies on workers moving in from other places who lack ties to the community and land. These workers are often housed in “man-camps” due to the isolated locations extraction occurs.

Call to Action!

Looking West Over Kings River Valley

Currently, Lithium Americas is still waiting on their reclamation bond to be approved before starting construction/destruction at the site. It is a little hard to calculate the cost of intergenerational pollution. The McDermitt Tribe is engaging in their sovereign right to reconsider their relationship with the company, having recently withdrawn from the Project Engagement Agreement with the company. The fire continues to burn at the protest camp. The ranching community continues to meet weekly to organize the defence of their livelihoods.

At the same time, the Biden administration’s climate plan calls for an aggressive increase of domestic lithium mining. Nevada Governor Sisolak is committed to ramping up lithium extraction in the state. Mining companies are greenwashing and re-branding themselves as environmental saviors. Many big environmental groups are also promoting domestic lithium mining as a way to limit the impacts of western corporate imperialism in regions with less stringent regulations. However, colonialism is not a completed project. Mines in Nevada continue to be on Indigenous lands. Paiute, Shoshone, Goshute, and Washoe people continue to work to protect lands that have sustained them for thousands of years.

I do not want to disparage climate science. I do want to make a point that when we are narrowly focused on carbon counting, we lose sight of humanity, and risk implementing “solutions” that continue the social oppressions and ecological degradation which drive the very problems we aim to solve. Yes, let us continue to listen to the best science and use our heads. We must also come to these problems with our hearts, and must listen to communities and leaders from them who know all too well the impacts of mining.

I would like to thank Myron Smart for educating us about his home and the frontline impacts of lithium mining. I hope that those reading this will act from their minds in knowing we cannot remain on the path of the dig burn dump economy which drives climate change, and will also act from their heart and know that we cannot sacrifice communities against their will so that we may maintain the conveniences we’ve grown used to while attempting to reduce carbon emissions.

For those interested in learning more, or visiting the protest occupation camp, please visit protectthackerpass.org

PLAN is committed to continued support for those protecting Thacker Pass. To stay up to date on this issue and all of PLAN’s work across social justice in Nevada sign up here to receive our weekly newsletter.

With humble gratitude,

Ian Bigley

Lithium Mining Position Statement

PLAN believes in a world where people come before profit. We oppose insanely destructive gold projects, which obliterate the land for material that is primarily used for jewelry. However, the growth of the lithium mining industry to supply materials used in renewable energy technology poses a more complicated ethical calculation since the materials provide a public good to fight climate change.

We do not believe that the benefits of lithium mining open the door for unchecked destruction of our land, air, and water. Furthermore, recycling capacity for lithium batteries isn’t scaling with new extraction, so we must increase recycling capacity to ensure lithium batteries do not go to hazardous waste landfills. PLAN has two primary considerations when it comes to supporting or opposing lithium projects.

Community Informed Consent.

- Have the affected communities been adequately informed about the potential range of impacts resulting from a mine to make a reasonably informed decision?

- Have the affected communities made an independent decision to consent to the project?

- Will the affected communities have a say in the distribution of economic benefits?

Irreversibility of Impacts

- Will the mine have impacts that can not be un done; perpetual acid drainage, destruction of cultural sites, extinction of species, impacts to migration routes?